Contrairement à ce qu’on répète en général, ni Smith ni Carlos n’appartenaient aux Black Panthers, cette organisation radicale qui militait aux Etats-Unis contre la situation injuste faite aux Noirs; mais la mort de Martin Luther King le 4 avril 1968, puis celle de Robert Kennedy le 6 juin de la même année, les incitait l’un et l’autre à agir à leur niveau, en faisant un geste symbolique qui, ils en étaient persuadés, aurait un retentissement dans le monde entier. Les JO n’offraient-ils pas cette occasion inespérée?

Il faut ajouter qu’une rencontre fut très certainement déterminante pour passer à l’acte: celle de Harry Edwards. Ce professeur de sociologie, ancien athlète, avait fondé juste un an avant, l’Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR), dans le but d’organiser un boycottage des JO; pour lui, il n’était plus question de gagner des médailles pour un pays qui refusait d’intégrer la minorité noire. Voici comment il justifiait sa position au New York Times en 1968:

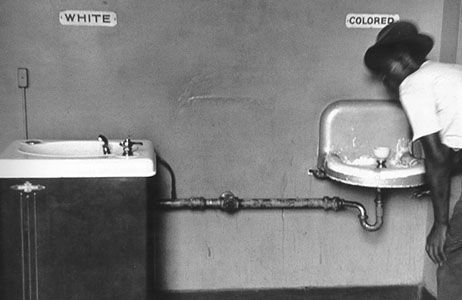

| "For years we have participated in the Olympic Games, carrying the United States on our backs with our victories, and race relations are now worse than ever," he told the New York Times Magazine in 1968. "We're not trying to lose the Olympics for the Americans. What happens to them is immaterial.... But it's time for the black people to stand up as men and women and refuse to be utilized as performing animals for a little extra dog food." |

Mais plus fondamentalement, et au milieu d’autres revendications générales, l’OPHR s’en prenait directement au Comité international olympique (CIO) et surtout à sa présidence… Fondé en 1896 à l’issue des jeux d’Athènes, le CIO est l’autorité suprême du mouvement olympique. Celui-ci s’est doté d’une charte adoptée par les membres du CIO et qui dit ceci:”l’olympisme est une philosophie (…) alliant le sport à la culture et à l’éducation, (il) se veut créateur d’un style de vie fondé sur la joie dans l’effort, la valeur éducative et le bon exemple et le respect des principes éthiques fondamentaux universels”. On remarque donc que si le concept de droit de l’homme ne figure pas explicitement dans la charte de l’olympisme en revanche, on y trouve une défense des principes moraux universels. Selon Harry Edwards et son OPHR, ces nobles principes ont été largement dévoyé par le racisme du président du CIO, Avery Brundage (1952-1972). Il faut se rappeler qu’en tant que président du Comité américain, celui-ci avait déjà milité pour la participation des Etats-Unis aux Jeux de Berlin organisés par les nazis en 1936. Ce flagorneur zélé avait même retiré les athlètes juifs de l’équipe américaine du relais 4 fois 100 mètres.

Brundage pouvait donc à bon droit se sentir directement visé par ces trois sprinters d’exception exhibant le badge de l’OPHR. Le lendemain, il demanda l’expulsion de Smith et Carlos à la délégation américaine. Leur carrière était terminée… ils devinrent entraîneurs d’athlétisme. Mais qu’est-il arrivé à Peter Norman ? Au départ, celui-ci ne devait pas être impliqué, mais ayant surpris Smith et Carlos évoquer leur projet dans les vestiaires, il leur avait exprimé son souhait d’accomplir lui aussi un geste de solidarité. Geste qu’il paya très cher, car le meilleur sprinteur de son pays, ne fut pas sélectionné en 1972 pour les Jeux de Munich et sombra ensuite dans la dépression et l’alcoolisme.